The locution “criminal organisations” works better than “organised crime” for drawing attention to variation along the following lines. Different categories of organisation have distinctive revenue streams, modes of committing or modulating violence, origin myths, cultural practices and narratives of self-justification.

They also exist at different scales, and manifest differential capacities to penetrate and exploit one another. Perhaps most important are the different historical trajectories out of which the different categories emerged. What follows is a very brief outline of how I am thinking about these trajectories with reference to the following kinds of criminal organisation: bands of rustlers and pirates; urban gangs; white-collar conspiracies; mafia-like fraternal sodalities; and smuggling enterprises, including “drug cartels”.

The nineteenth century commoditisation of land and labour, in turn propelled by property law, the hegemony of industrial capitalism and European imperialism, nourished – even if it did not generate – the first three categories: bandits or pirates; gangs; and conspiracies of fraudsters. Mafias were of a larger scale, achieving inter-generational consolidation after the 1860s. Forming amidst the disorder of banditry and gangsterism, mafia cliques asserted an elite status vis-à-vis bandits and gangsters, some of whom they deployed in extortion rackets. But the historical trajectory of mafias was limited to places such as Italy and Japan, where political and economic leaders, ambitious to close the gap with the leading capitalist hegemons of the time, tolerated – and rewarded – mafias as adjuncts to the project.

Smuggling enterprises or “cartels” took off somewhat later and under different circumstances. Whereas property law and the hegemony of industrial capitalism nourished the above-noted criminal organisations, prohibitionist law and the hegemony of contraband capitalism were the cartels’ decisive fuel. For Peter Andreas, author of Smuggler Nation: How Illicit Trade Made America, “contraband capitalism” begins with entrepreneurial vitality vis-à-vis the laws of states. Heavier policing and stiffer penalties only provoke more aggressive or creative avoidance strategies – a dialectic of law enforcement and illegality. If tariffs and taxes, regulations and borders, conjure contraband capitalism, however, they do not hold a candle to prohibitionist laws. This is because prohibitionism ups the dialectical ante, pitting not only state-makers against entrepreneurs, but also intensely moral-cum-legal proscriptions against expanding markets of desire. Occasionally there is a moral consensus underlying the proscriptive bans; when such consensus is absent, smuggling enterprises thrive. What Nancy Scheper-Hughes calls the “rotten trades” – enterprises that traffic in sex workers, animal and human body parts, migrants and endangered species – are good examples. Addictive substances, so often fraught with moral contestation, are even better.

If North Atlantic Europe was the cradle of industrial capitalism, the United States was the centre of gravity for the “rise” of the contraband variant

If North Atlantic Europe was the cradle of industrial capitalism, the United States was the centre of gravity for the “rise” of the contraband variant. White colonial settlers and their descendants corralled, squeezed or exterminated the Native American population, appropriated its land for “improvement”, then imported wave after wave of “alien” labour from abroad. Whether African-descended slaves who produced plantation crops; erstwhile peasants from Ireland, Germany, Southern and Eastern Europe who worked in factories and mines; immigrant Chinese who built railroads; or Mexicans who harvested crops – all risked being defined as uncivilised, sexually aggressive, vengeful and rebellious, notwithstanding the demand for their labour. Descendants of the white settlers convinced each other that consumption of alcohol and drugs intensified the threat; prohibitionist law criminalised both these psychoactive substances and the “dangerous” workers with whom they were associated. A spectacular consequence was the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution that, from 1920 until 1933, forbade the manufacture and distribution of alcoholic beverages.

From the late nineteenth century, the US market for drugs grew by leaps and bounds – a reflection of the transformation of everyday life with industrialism. Abundant supplies from abroad and an expanding commercial culture contributed to the dynamism. Growing medical awareness of habit-forming substances, however, together with temperance movements, resulted in a cascade of restrictive actions.

An increasingly imperial US also played a leading prohibitionist role internationally. Already in 1908, the US prohibited opium smoking in the Philippines, its newly acquired possession. One year later, Congress passed the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act that targeted opium imports smoked by Chinese immigrants; it was the opening salvo in America’s “war on drugs”.

In 1909 Congress passed the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act that targeted opium imports smoked by Chinese immigrants; it was the opening salvo in America’s “war on drugs”

Although the 1909 act left medicinal opium off the table, it advanced the concept of a ban. This was reinforced in 1914 by the Harrison Act, which regulated and taxed opiates and cocaine. Strengthened by subsequent court rulings, the law further constrained doctors from prescribing maintenance supplies to addicts, closed already prison-like hospitals for detoxification and recovery, and shifted the framing of narcotics abuse from public health to criminality. Notwithstanding agitation to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment, whose enforcement became ever more untenable over the 1920s, the US sent vocal drug prohibitionist delegations to Shanghai, The Hague and Geneva. Its delegation to the 1931 Geneva Convention included the mover and shaker of US drug policy, Harry Anslinger, who became the Commissioner – for 33 years – of the new Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Anslinger was not only a radical prohibitionist; he believed that all nations should establish as legal principle the eradication of habit-forming drugs at their source – a stunningly unworkable program that was, however, eventually enshrined in an international prohibitionist regime, established by the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs in 1961.

Contraband capitalism took off in the early twentieth century and has thrived ever since. Entrepreneurs of smuggling enterprises had a striking advantage. By mobilising already existing criminal organisations, mafias among them, they rapidly assembled such telling assets as illegal firearms, clandestine routes and vehicles, protected hideouts, trusted couriers, and channels for laundering money. An analogy would be the acceleration of the industrial manufacture of textiles on the backs of “putting out” systems , in which merchants distributed spinning and weaving equipment to households. Like these systems, criminal organisations, whatever their distinctive origins, were transformed as a consequence of the synergism, in this case drawn into a (seemingly undifferentiated) swirl that we too easily label “organised crime,” occluding the complexity of how we got here.

Jane Schneider is Professor Emeritus at the City University of New York (CUNY) and former head of the PhD Program in Anthropology.

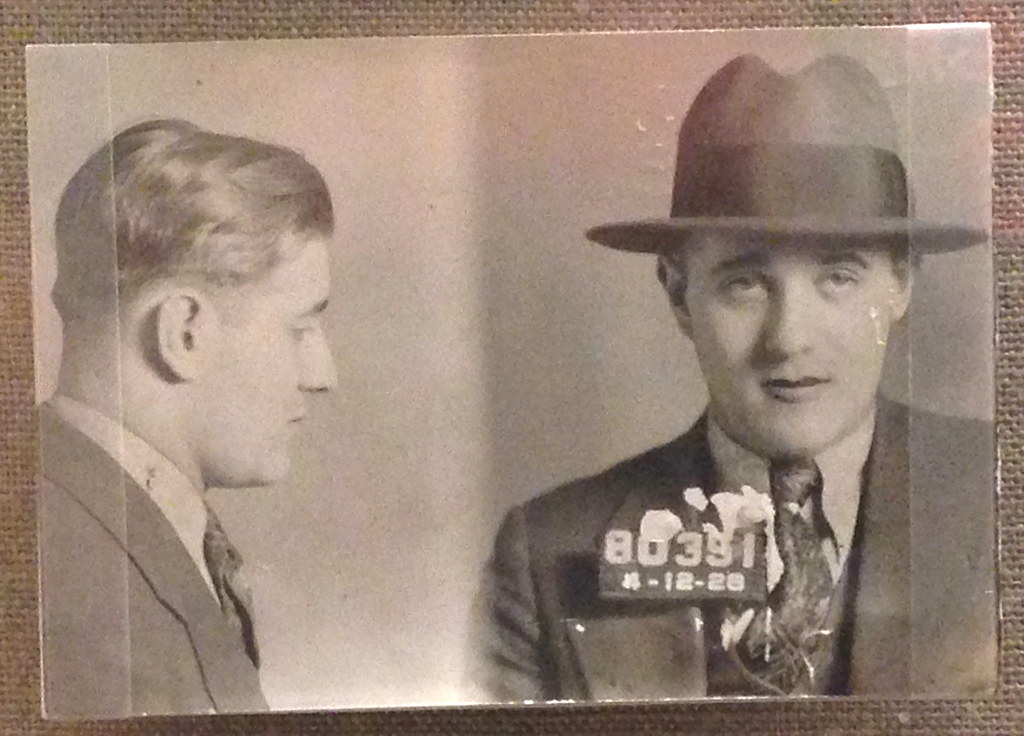

Main Image Credit: Edward Headington, via Flickr.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of RUSI or any other institution.