Graphic crime scenes accompanied by figures depicting unprecedented homicides rates continue to dominate the Mexican media landscape. In Mexico, violence and its causes have dominated almost all areas of public discussion for the last ten years and countless pages have been devoted by journalists, fiction writers and academics to dissecting the so-called Mexican insecurity crisis. Each of these three mediums are important forums for public understanding, yet they also share several key limitations that require new critical thinking skills. Namely, the crisis demands that journalists, writers and academics deconstruct and think creatively about the issue.

The first limitation in the conventional thought about Mexico today isthe belief that increasing violence can be attributed solely to two primary factors: turf wars between drug trafficking organizations and weak state institutions. This somewhat lazy line of argument fails to take into considerationthe general incidence of violence and criminality across all societies. Moreover, it also takesforgranted that violence in the country only comes from confrontations between narcos and the Army or police, ignoring any other potentially violent agents in configurations where drug trafficking could have a more marginal role. In this narrative, drug trafficking organisations are also somehow responsible for filling an alleged ‘vacuum’ created by the paucity oflaw enforcement agencies or even the State overall, to the detriment of considering other possible arrangements between those actors, including the possibility that the relationship between both variables can be symbiotic or semi-cooperative.

Secondly, the conflation of disparate phenomenon such as ‘organised crime’, ‘drug trafficking organisations’, ‘cartels’, ‘narcotráfico’ and ‘narcos’ means that all many different types of violence are labelled interchangeably. As Luis Astorga has written, when it comes to this kind of violence, ‘rhetorical fireworks [often] matter much more than conceptual accuracy’ (276). Ultimately, the term ‘narco’ has become a multi-purpose prefix used to describe almost anything associated with drug trafficking.

Ultimately, the term ‘narco’ has become a multi-purpose prefix used to describe almost anything associated with drug trafficking.

For instance, around one third (59) the 175 words in the Glossary of Terms in George W. Grayson’s book Mexico: Narco Violence and a Failed State? use the prefix narco or some Spanish derivative (p.310-313). Thus, it is possible to find terms as diverse as narcoabogados (lawyers who defend drug dealers), narcoasesinatos (drug-related killings), narcoaficionado (drug baron who is a sports fan), narcobautismo (the baptism of the child of a cartel leader), narcoconcursos de misses (a beauty contest sponsored by capos) and narcomonjas (religious sisters involved in drug trade), among others.

Third is the characterisation that drug traffickers, their organisations, dynamics, incentives and resources are uniform and recurrent. This leads to an image of the narco that (re)produces reductionist and simplistic prejudices. As Oswaldo Zalava has written, regardless of the area in which they operate, or the activities they carry out, “any narco is all the narcos” (p.33). What is sure is that the combination of these three superficial and simplistic representations impedes an accurate understanding of the issue in Mexico.

What is sure is that the combination of these three superficial and simplistic representations impedes an accurate understanding of the issue in Mexico.

The dominance of these representations can be attributed to at least two factors: a lack of empirical evidence and the habit of taking dominant frames of reference for granted across time and space. This lack of empirical evidence owes in part to the inherent difficulty of obtaining accurate sources on an activity which, by its nature, wants to remain hidden.

Three main sources do exist, however: 1) official versions and figures; 2) press coverage; and 3) accounts by criminals themselves. The temptation for each of these sources to quote one another often leads to circular reporting, where imprecise information is repeatedly circulated until the original source becomes obscured. As a consequence, each ‘new approach’ tends to be based on the same statistics, and suffer from the same potential inaccuracy, insufficiency and bias. This issue is compounded by the lack of rigour amongst some media sources: after all, the guidelines used by journalists differ significantly from the standards social scientists seek in their own fieldwork. Likewise, whilst it may be tempting to seek information from alleged drug leaders or minor profile criminals (where we can find them), the motives behind this decision require a degree of caution.

All of this begs the question: how can we assess the causes of violence linked to drug trafficking in Mexico without falling into the same traps? Here, two critical thinking tools could be useful: deconstructing and thinking creatively about the issue.

A creative approach is useful because it might drive us to innovate new entrances to fieldwork, to seek out unexplored archives and marginalised actors. For instance, despite the importance of businessmen as economic power holders and centrepieces of the drug trafficking configuration, these actors are rarely investigated. Where they are investigated, the common perspective regarding the rapport between businessmen and the narco is to consider them as either victims of extortion or money launderers.

My experience conducting fieldwork among the business sector in Guadalajara provided me with a less well appreciated perspective: for more than thirty years, businessmen and their families have been sharing social spaces with the so-called narco-families, growing up in the same exclusive quarters, attending the same schools or sports clubs and even marrying their descendants. Such proximity challenges the stereotypical image of the narco and businesspeople as either belonging to the legitimate or illegitimate side of the spectrum.

Likewise, a more creative approach might force us, as researchers, to question our dominant levels of analysis. For example, our insistence on national scale studies in a country as huge and diverse as Mexico might lead us to overlook precious data that could be gathered at a local level.

To dislodge dominant paradigms, researchers should begin by asking themselves: why and how do I know what I think I know?

Meanwhile, deconstruction is also an underutilised critical thinking skill. To dislodge dominant paradigms, researchers should begin by asking themselves: why and how do I know what I think I know? This question might force us to question the assumptions underpinning certain terminology such as narcos, for example. So, the next time we are tempted to repeat that a Mexican narco is an illiterate or poorly educated individual unable to transform his ill-gotten gains into cultural capital, we might instead be tempted to open the black box behind the narcos’ label (p.265).

Drug trafficking and its effects on insecurity and violence dominate both academic and non-academic discussions about Mexico. However, a lack of empirical data and the tendency to indulge in circular reporting means it is difficult to discuss Mexico without falling into the same simplistic and reductionist explanations. Here, the application two critical thinking tools could be useful: deconstructing and thinking creatively about the issue. Crucially, to dislodge dominant paradigms, researchers must begin by asking themselves: why and how do I know what I think I know?

María Teresa Martínez is a PhD Candidate in Political Science (Comparative Political Sociology) at Sciences Po, Paris. Among her research interests are white collar involvement in the protection market, non-state violent actors and corruption, with a regional specialism in Mexico. She has conducted fieldwork in cities such as Guadalajara, Querétaro and Morelia.

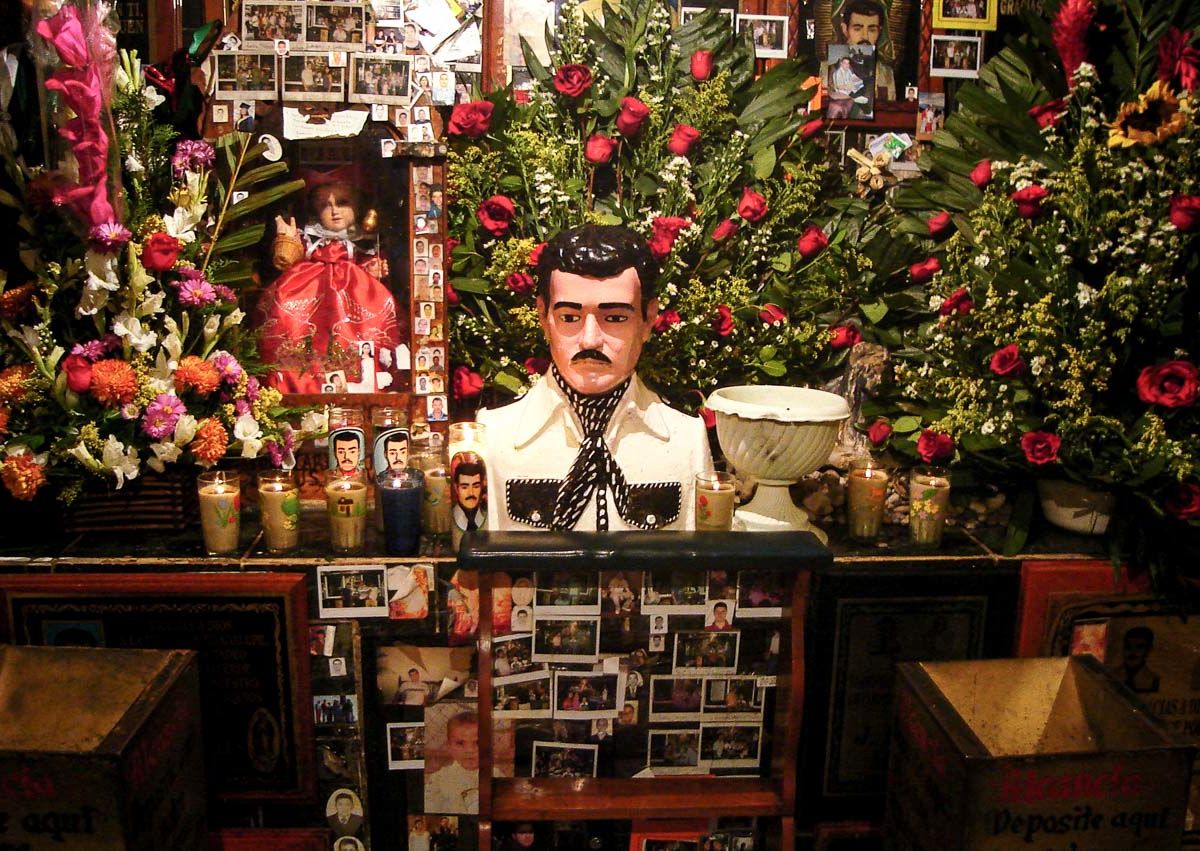

Main Image Credit: David Boté Estrada, via Flickr.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of RUSI or any other institution.