Being a criminal in Rio de Janeiro has never been a safe business, but this year it’s more dangerous than ever.

On February 16 2018, Brazil’s federal government took over the administration of security in the state of Rio, normally an exclusive domain of the State government. President Michel Temer signed the decree, declaring that this ‘extreme measure’ was necessary because organised crime had become ‘a metastasis spreading over the whole country… [that] almost took over the state of Rio’. This act marks the beginning of an unprecedented federal intervention in Rio de Janeiro’s public security. Although the Armed Forces have often operated in Rio against organised crime, they have always done so in cooperation with the State government. Yet this time is different, and the federal government have assumed command over the local security forces: a situation that has not been seen since the end of the military dictatorship in Brazil and the adoption of the current constitution, thirty years ago.

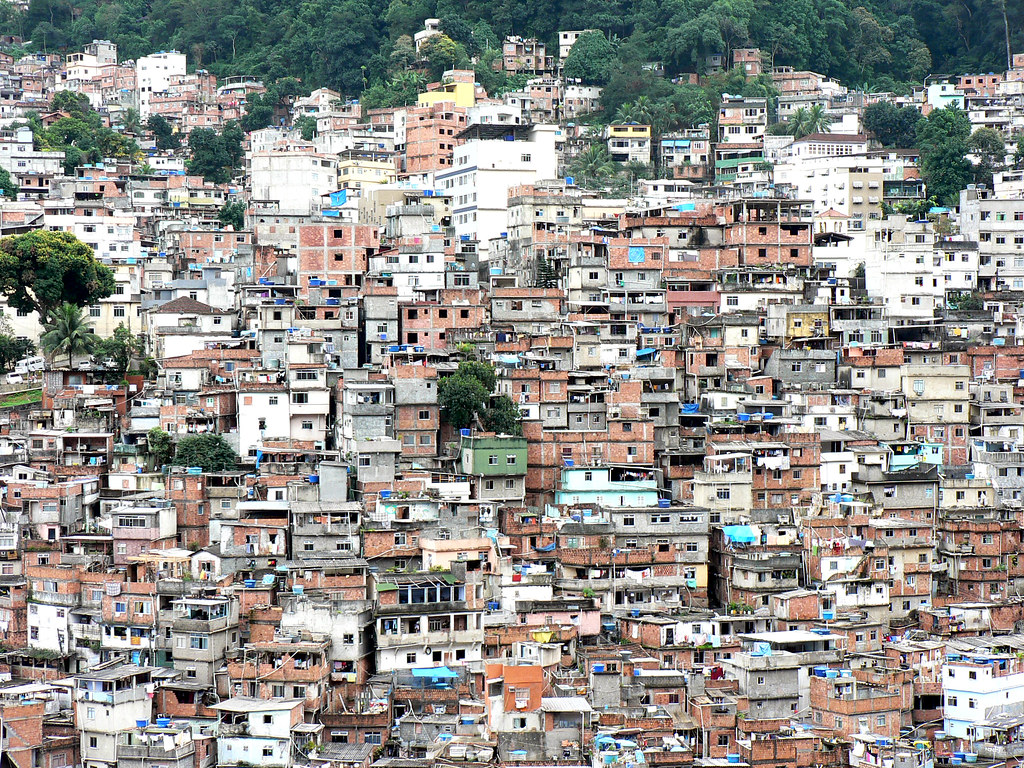

It is not yet clear what results these extreme measures will achieve. On paper, the intervention certainly gives the government the leeway to bring an even fiercer fight to the organised criminals, but it is also bound to meet formidable resistance from Rio’s well-established criminal groups. The most visible – and most targeted – among these groups are the drug trafficking alliances, called ‘factions’, whose main business is dealing in marijuana and cocaine from heavily defended points inside the city’s slums (favelas). It is these factions who have learned many hard-fought lessons from the city’s history of military involvement in domestic security affairs.

From the outset, the federal intervention was not meant to impose purely hardline or militarised security policies. The federal government also announced that it would bring about a sweeping reform of the local police forces, with a particular attention devoted to uprooting corruption on the ground. However, what has been done up to now has yet to live up to the blueprints. The operational methods of the security forces, mostly consisting in raids by tactical elite battalions or short-lived occupations in the favelas, has barely changed since the federal government took over. The only exception to this are the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), Rio’s experiment with ‘counterinsurgency’ forces which have actually been downsized due to lack of manpower and loss of local control. So far, the promises of vast security sector reforms have only produced a strategic plan that took four months to be written and put forward no long-term ideas.

At the same time, the federal government also marketed its intervention as an opportunity to carry out a harsher crackdown on organised crime by imposing fewer restraints on the use of force. For example, some ministers called for sweeping investigation and search powers that could cover entire neighbourhoods. Although these ideas were soon discarded, the very nature of having soldiers operating against organised criminals inherently indicates that there will be less oversight from judicial authorities.

This is because allegations made against members of the Armed Forces in Brazil can only be examined by military judges, a fact that may lead to eventual impunity according to Amnesty International. Arguably, the authorities even seemed to recognise this, admitting that ‘undesirable things, even injustices’ might occur during the intervention. For this reason, too, Army Commander Eduardo Villas Bôas asked that a ‘Truth Committee’, similar to the one established in 2011 to investigate crimes committed during the military dictatorship, should not take place in the future; a request contested by human rights groups and prosecutors.

From the outside, all of this may look like really bad news for Rio’s criminal underbelly. In reality, however, there is likely to be little despair amongst local factions. Over the past 25 years, faction members have learnt three main survival lessons that will help them to weather the storm. And whilst these lessons might not allow individual criminals to live another day – one of the main effects of the intervention has so far been a 46% yearly increase in deaths following police intervention – their businesses will most likely live on.

The first lesson is, simply, to hide. This is not so different from what insurgents and rebel fighters do in asymmetric conflicts, a similarity that has not passed unobserved among some practitioners in the Brazilian Army. Here, traffickers have the advantage of not wearing uniforms or distinctive signs and whilst some factions of course have names, symbols, and mottos that strengthen their identity internally, most traffickers learnt long ago that, in general, it is better not to advertise your gang membership in public.

In a set of instructions reportedly drafted in the early 1980s, avoiding distinguishing tattoos was already one of the twelve most important rules of the ‘good bandit’. This means that, in general, traffickers are indistinguishable from other teenagers/young adults living in a favelaand can thus easily ditch their weapons and blend in among local residents if they are being pursued. The ability to blend in, coupled with the advantage of hidden defensive positions and extremely complex terrain, makes it extremely difficult for security forces to recognise suspects in a pursuit. Ultimately, it is only local intelligence and investigative work that can overcome these obstacles, but this is exactly the kind of knowledge that Army soldiers, who come from all over Brazil, cannot reap.

The second lesson is that outside forces are often not strong enough to occupy all the irregular and dense space of a favela. Factions in Rio have therefore repeatedly demonstrated that it is possible to weather the initial effects of military occupation, carve marginal spaces for business, and eventually fight to regain lost territory. This is what has happened in the past seven years in the favelas(or groups of them, known as complexos) such as Rocinha or Alemão. Although both of these favelaswere occupied with the assistance of Brazil’s Armed Forces and policed by the newly established UPPs, over time traffickers have managed to create areas in which the police are increasingly reluctant to operate, and in which criminals could again openly display weapons. As a consequence, police estimates from August 2017 showed that UPPs only remained in full control of 5 out of 39 favelas. Of the four UPPs present in Alemão, two had lost more than 55% of their territory and in Rocinha, another estimate from September 2017 showed that 51.6% of the territory was outside the reach of regular police forces.

This can equally be the case where police occupations by the Armed Forces are involved. The recent occupation of Complexo da Maré, an ensemble of 16 favelas, shows just that. The Armed Forces occupied Maré for 15 months, between 5 January 2014 to 30 June 2015, costing around R$559.6 million (£113.5 million pounds) and involving 23,000 soldiers. These resources led to 674 arrests and 1356 reported seizures of drugs, weapons, and vehicles. Yet whilst in that period murder rates decreased by 75% and trafficker profits by 79%, the criminal groups did not simply come to an end.

At first, the criminals simply hid inside the Complexo, exploiting their local knowledge and networks, and observing the soldiers’ behaviour. Then, they began to tease them with regular shootings and the occasional grenade. On average, soldiers experienced two attacks daily and the Army even suffered its first casualty on home turf since 1972. Eventually, midway into the occupation period, traffickers were able to establish areas of armed control where they could openly display weapons, check on who was coming in and out of the individual favelas, and even carry out attacks on each other. It is perhaps no wonder then that some soldiers cheered on their buses when they handed Maré back to the local police force. With this withdrawal, the factions quickly returned to the old modes of operation. Just a week after the end of the occupation, the Military Police deployed tactical elite battalions like BOPE (Special Police Operations Battalion), where a 20-year-old man was promptly hit by a stray bullet during the operation.

Even on those rare occasions when hiding and carving up small, local enclaves has proved impossible, there is still one last viable option: escape. This was always seemingly the last option in places such as the Complexo do Alemão. This complexo came to be occupied following intelligence that indicated an intolerable string of attacks against police stations, buses and regular citizens had come from the leaders of the Red Command faction hiding there. On 28 November 2010, 2,600 police officers and soldiers proceeded to occupy the area, which, by then, was hosting factions from across Rio who had already escaped from police operations nearby. While there were several shootings in the preceding days, with 37 people killed between 21-28 November, most Red Command members present in Alemão managed to escape, this time through a minor exit road..

Security forces did little to prevent this, as the ‘pacification’ of Alemão was already a major task by itself and required all available resources. The gang members that escaped then made their way to another favela in Jacarezinho; and then, when that was occupied too, they migrated to Covanca, a favela in the Western zone of the city, where they overpowered the local paramilitary group and established their own businesses. Other traffickers simply left for cities in the metropolitan region that were untouched by the pacification process, like Niterói, Macaé, and Japeri. As a result, these occupations have reproduced – albeit on a metropolitan scale – the same kind of displacement effect caused by U.S. drug eradication policies in Latin America. This is the so-called balloon effect, a long time enemy of law enforcement agencies that has effectively arrived in Rio too.

Drug factions have learnt these three lessons (hide, fight, escape) the hard way. Over the past ten years, many of their members have opted for one or more of these courses of action and those who did not have been either arrested or killed. Unless the Armed Forces and the police evolve tactically and strategically, it is unlikely that those who remain under this new occupation will need to deviate from these lessons. So far, this federal intervention looks like more of the same, pointing to the unlikelihood of an operational change in Rio. The factions, or at least their businesses, will surely survive well beyond the end of this intervention.

Andrea Varsori is a PhD candidate at the Department of War Studies, King’s College London, as well as the Editor-in-Chief of Strife Journal and Blog. His research focuses on urban armed groups in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. In particular, he seeks to explain their resilience through an evolutionary/ecological lens, by analysing the history of their internal changes. Andrea holds an MA in International and Diplomatic Sciences from the University of Bologna. You can follow him on Twitter @Andrea_Varsori.

Main Image Credit: World Resources Institute, via Flickr.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of RUSI or any other institution.