The rise of global authoritarianism whips up a perfect storm, aiding the evolution of transnational organised crime.

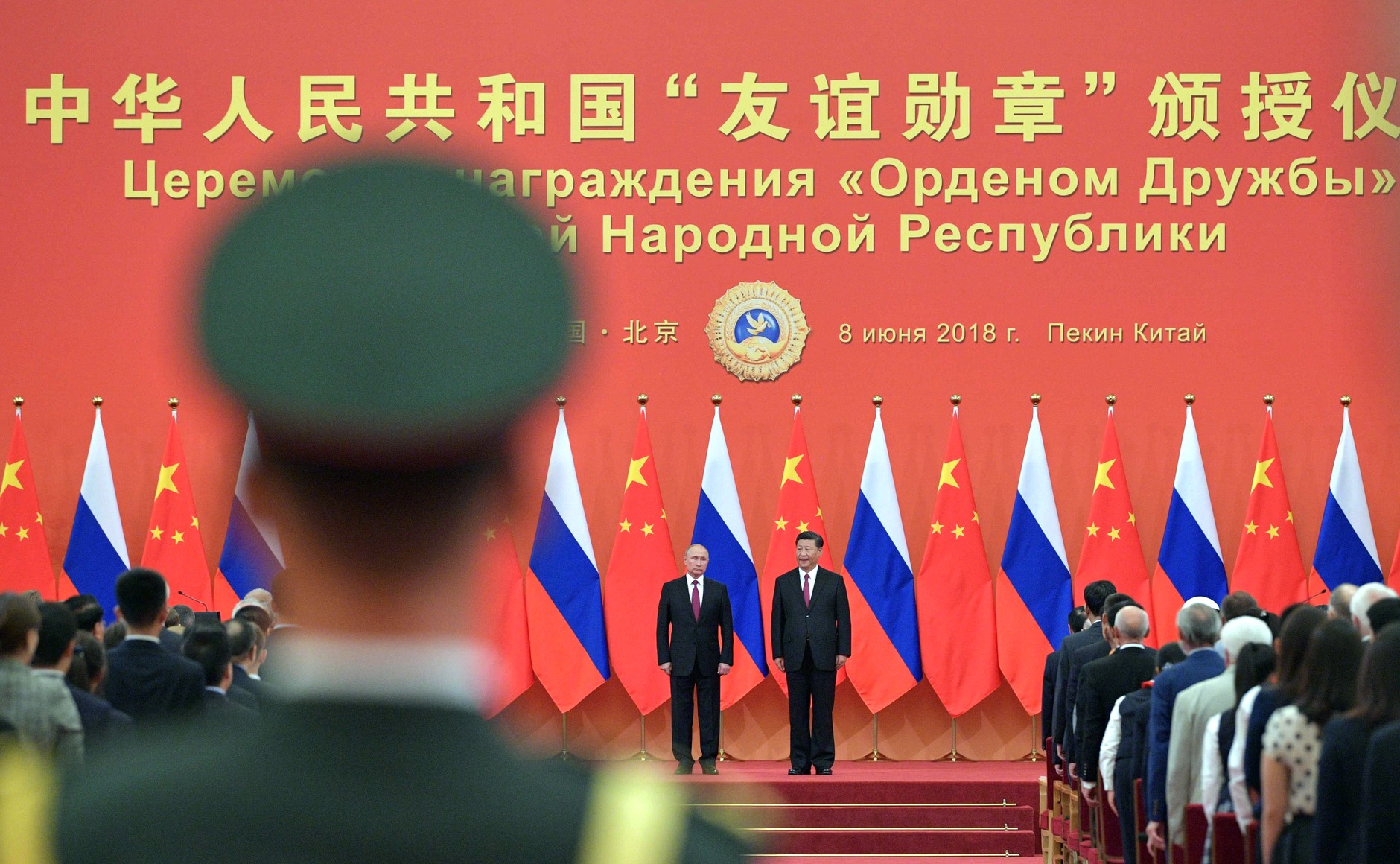

Transnational organised crime is becoming more organised by the day. Why has the evolving ground reality already surpassed the existing definitional and semantic understandings of this phenomenon? Transnational organised crime is a term, which reminds us of crooks, cartels, mafia, the underworld, traffickers, and the like. Instead, what if the state, supposed to be the defender against illicit activities, becomes the frontrunner of transnational organised crime? Less attention is paid to transnational organised crime in the context of the rise of global authoritarianism. This context highlights an increasingly belligerent Russia and China with their allies in the anti-democratic fold creating a sphere of influence, or a geopolitical sphere of impunity against the post-World War II rules-based world order.

Autocracy and Criminality

Autocracies are fundamentally criminal since the rule of law does not govern them. Forming an autocratic geopolitical sphere devoid of democracy, the rule of law, free media and civil society, or a healthy debate sanctions transnational organised crime. First, this autocratic sphere of interests collides head-on with liberal democratic values upheld by the rule of law. Second, it aims to overrun the post-World War II rules-based world order by sabotaging the rules of fair games in economic and other undertakings. The evolution of transnational organised crime cannot be understood apart from this context. Moreover, authoritarian contagion and authoritarian diffusion encourage kleptocracies, mafia states, narco-states, failed states, and regimes with autocratic tendencies. How exactly would this context shape the evolution of transnational organised crime?

Researchers understood transnational organised crime as the organised criminal acts of non-state actors committed with economic motives against nations across national borders. The understanding of transnational organised crime as the (i) non-state actors, (ii) driven by economic motives to (iii) act against the nation-state is still the dominant understanding. At least, it is the dominant semantic depiction to date. The debate on transnational organised crime caught up with reality when researchers uncovered its links to international terrorism. The consequent debate focuses on how these two phenomena collaborate. Transnational organised crime and its affiliates never stopped diversifying while vying for political control to create safe havens. Shelley defines transnational organised crime as the ‘new authoritarianism’, concerning its challenge to the nation-state. However, this reality was subjected to rapid changes. While transnational organised crime still challenges the state, how the state apparatus is absorbed into the domain of transnational organised crime? Authors such as Shelley (2014), Albanese (2018), and Desmond (2019) explain the role of ‘corruption’, aiding the criminal conquest of the state apparatus. However, what if corruption is the status quo (in the absence of the rule of law), as was seen in autocracies and regimes with autocratic tendencies?

Transnational Organised Crime 3.0

Organised crime exists on the margins of every society, and corruption is in varying degrees deep-seated in every nation. All these are certainties, but with an exception—it is not possible to fight the rise of global authoritarianism without fighting transnational organised crime curated by it. When we examine the evolution of transnational organised crime, especially in the context of the rise of global authoritarianism, there is something more than mere corruption, something fundamental, which not only creates favourable conditions but also incubates the next big thing, i.e., transnational organised crime 3.0 (TOC 3.0). This is the version of transnational organised crime in the context of the rise of global authoritarianism in the post-9/11 world. The context is clear; the time frame is definitive, and the main driver is the intrinsic impunity of the autocratic sphere of power in the absence of the rule of law. The rational curators are the autocracies and their allies.

The timeline of transnational organised crime can be traced back to the 1970s as organisations such as Italian ‘Ndrangheta started their global money laundering operations. The second phase began in the 1990s when transnational organised crime seized the opportunities offered by an increasingly globalised world. Now, in the post-9/11 world, the rise of global authoritarianism brings a fundamental difference, offering a geopolitical sphere of impunity to encourage a criminal challenge to democracies governed by the rule of law. This indicates an emboldened phase in the evolution of transnational organised crime.

What, then, is the relationship between the state and transnational organised crime? The state is still at the receiving end of transnational organised crime. The state faces daunting challenges in the face of increased cross-border criminal activities. Corruption continues to act as a medium, which allows transnational organised crime to infiltrate the state. Protracted conflicts in many parts of the world created grounds where transnational organised crime can converge with terror groups. Researchers such as Naim (1995), Kupatadze (2015), and Godson, Olson, and Shelley (1997) analyse how the state becomes not a victim, but a sponsor of transnational organised crime. Kleptocracy, defined as ruled by thieves, is a phenomenon entangled with mafia states, narco-states, failed states, autocratic regimes, and regimes with autocratic tendencies. Chayes (2015) explains how the state operates as an organised crime cartel, denying its citizens’ rights.

The global organised crime index 2021 reveals an unsettling fact: ‘state officials and clientelist networks who hold influence over state authorities are now the most dominant brokers of organised crime’. We must recognise an increasingly salient aspect. This is how the rise of global authoritarianism transforms what has always been there, i.e., the infrastructure of transnational organised crime in a globalised world. How does the rise of global authoritarianism in defiance of the rule of law transform geopolitics? The rules will not inhibit the autocratic sphere of power since breaking and bending the rules is the autocrats’ way of wielding power.

What is the evidence? We have already seen how it works: China breaks the rules of fair play in international trade and champions the invasion of counterfeits and pirated goods worldwide. China and Russia get ahead through grafts and keep their hands in money laundering. Belarusian autocratic regime worked with human smugglers in Iraq to arrange illegal immigration to Poland to use it as a weapon of hybrid warfare against the EU. The Chinese state is complicit in the gruesome act of organ harvesting of the Falun Gong prisoners of conscience. The Taliban regime in Afghanistan arranges illegal human cargo and is back in business, harbouring international terrorists and taking part in narco-trafficking. Russia’s regime-sanctioned oligarchs funnel billions to the international property markets through tax havens and shell companies. In the border regions of Afghanistan and Pakistan, a transnational organised crime belt operates against the rules-based world order. All over the world, the rise of autocracy and its leverage of impunity emboldens mafia states, kleptocracies, failed states, narco-states, and regimes with autocratic tendencies. Transnational organised crime is becoming a weapon of choice in the hands of autocratic regimes for both strategic and politico-economic reasons.

However, there is a serious lack of studies on how authoritarianism rewrites transnational organised crime. The geopolitical rise of the inherent criminality of authoritarianism promises an evolutionary phase of transnational organised crime. Researchers need to catch up fast, both conceptually and empirically, to understand the evolution of transnational organised crime in the context of the rise of global authoritarianism.

Dr Chamila Liyanage is a researcher who works on the evolution of transnational organised crime in the context of the rise of global authoritarianism. She is a researcher of the Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET) and a Fellow of the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR).

Main image credit: Kremlin Ru

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of RUSI, Focused Conservation, or any other institution.