There are many ways to research organised crime and illicit enterprise. One of the most useful – yet underused – is historical research. This article argues that historical research should be used more to study criminal phenomena, and shows how its use highlights both the limitations of repressive short-term countermeasures and the strengths of longer-term socio-economic approaches in tackling organised crime. This further develops arguments made in Historical Perspectives on Organised Crime and Terrorism, a book I co-edited with John F. Morrison, Aaron Winter and Andrew Silke.

In an honest reflection of his own work, Donald Cressey (1967) suggested that researching organised crime is difficult due to:

“The secrecy of participants, the confidentiality of materials collected by investigative agencies, and the filters or screens on the perceptive apparatus of informants and investigators (101).”

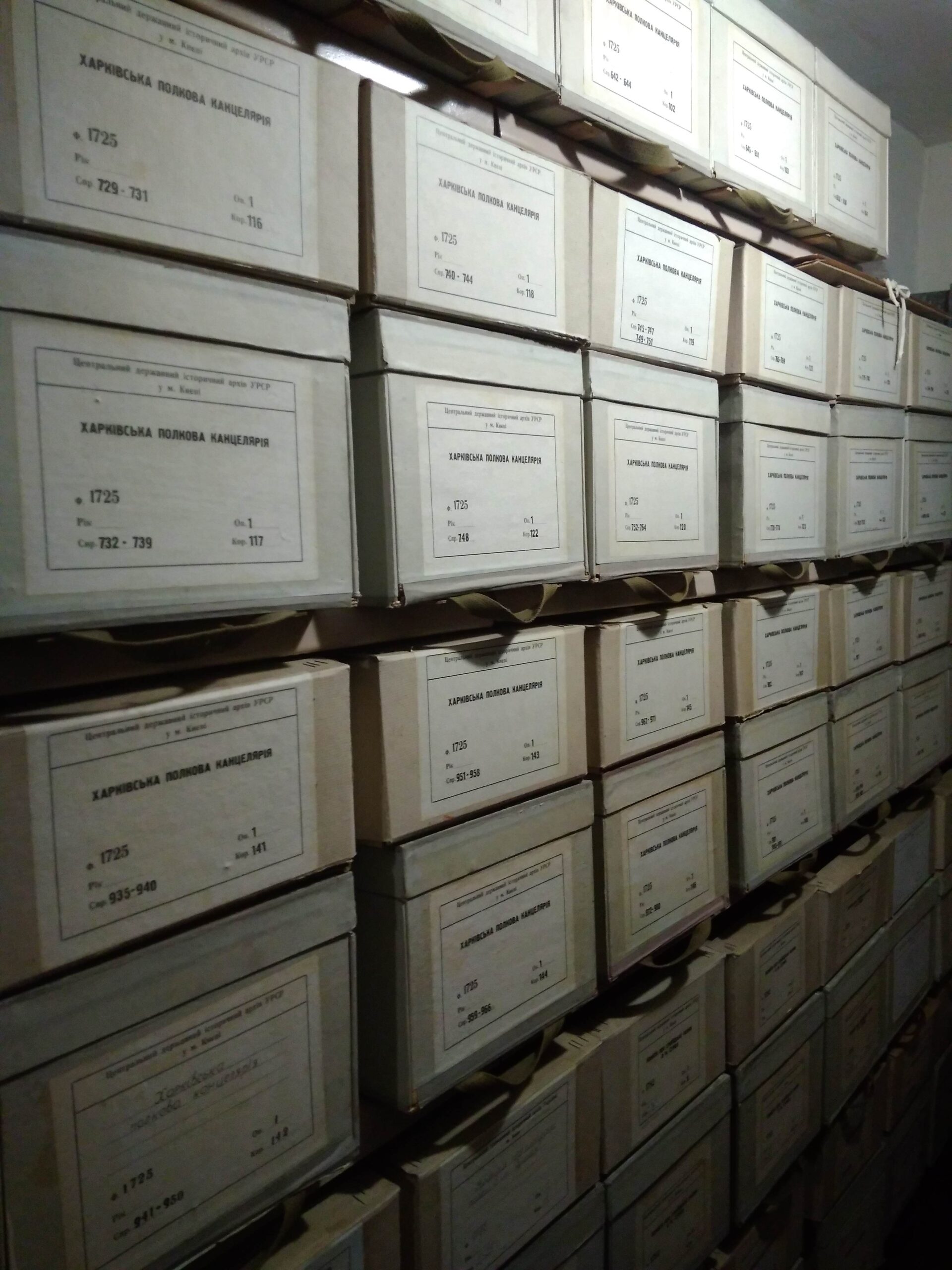

Government documents are by far the most commonly used data source in organised crime research. Closed/restricted documents can be difficult to access (unless the researcher has the right connections) and open-access documents do not always provide a balanced picture, largely because they are political documents for public consumption. As a result, closed/restricted documents which are later made available in government archives tend to be more reliable than documents generated for public consumption. The recruitment of offenders and victims can be complicated, and direct observation can be risky. Few organised criminals, illicit entrepreneurs, their victims or customers are willing to participate in self-report or victimisation surveys; two of the mainstays of criminological research.

This is not to say that such data collection methods are impossible; they have all been used to varying degrees by organised crime researchers. There is, however, a wealth of relatively easily accessible, yet underused, historical data sources on organised crime and illicit enterprise. The use of historical documents does not require ethical approval, is risk free (discounting the inherent loneliness of archives), and is becoming even more time and cost effective as more archives migrate online.

While the most obvious historical data sources are documents created by government bodies and then stored in archives, researchers can be more creative. We can explore documents created by enterprises sitting at varying points of the spectrum of legitimacy, cultural artefacts (i.e. dictionaries, fictional accounts, photographs, paintings, memoirs, music), or even gravestones and architecture. An example outside of the organised crime field: a friend’s house in Ireland has a bullet hole from a shootout between the IRA and Auxiliaries. Whenever I pass the house I plan how to gather and analyse similar images of revolution. (I won’t get around to doing this, so please take the idea. Even better, if you’re a student, email me about a PhD!)

Each of these historical data sources can produce research which is exploratory, descriptive, explanatory or interpretative. While historical research is most often used to provide context for current debates, it can also help make sense of structural changes and continuities. It can provide a deeper understanding of changes in a contemporary criminal group’s codes, norms or values, structure and operations, and chart the development of illicit markets (as does the excellent Smack: Heroin and the American City).

Importantly, historical research can challenge ‘common knowledge’ and correct commonly held misunderstandings about the past and the present. For example, several chapters in Historical Perspectives challenge the framing of organised crime as an ‘alien conspiracy’ which undermines ‘our way of life’. Robert Lombardo shows how the growth of Italian-American organised crime was a direct result of socio-economic conditions within the US. Lombardo, alongside chapters by James Densley and Ryan Gingeras, then demonstrates how ‘ethnic’ organised crime has often been enmeshed within networks of politicians, police officers and other ‘upperworld’ actors. Gingeras concludes his chapter with the observation that the Federal Bureau of Narcotics scapegoated foreign drug traffickers during the 1970s to divert attention from the ‘complicity and incompetence’ of US counternarcotic agents. Such lessons from the past could not be more relevant considering the current political climate of many countries, including the UK and US.

In terms of policy and practice, historical research can facilitate evaluation of patterns, mistakes and failures

In terms of policy and practice, historical research can facilitate evaluation of patterns, mistakes and failures. This can help us avoid unanticipated consequences. For example, a number of chapters demonstrate how countering organised crime often requires long-term strategic thinking rather than short-term goals, which may be immediately politically useful but fundamentally counterproductive. Two chapters respectively show how repressive, militarised, interventions against Burmese opium cultivation and Somalian piracy pushed communities further from state authority, further weakening state influence and inflating insurgencies.

The value of socio-economic development and counter-productivity of repressive or militarised interventions has been argued by others. A number of contemporary and historical studies highlight the necessity of gaining the cooperation of local communities in order to contain illicit enterprises. This often requires a longer-term strategy of political capital building and the avoidance of interventions which might weaken state–community relations. These studies include my own historical comparative research on preventing opium farming, Vanda Felbab-Brown‘s research on wildlife poaching and Chris Bowkett’s ethnography of Camorra extortion (see here for similar arguments applied to counter-terrorism).

The kingdom of Thailand provides a good example of the benefits of socio-economic development as opposed to repressive law enforcement. During the 1960s, the military attempted to forcefully eradicate opium in areas with high communist insurgent activity. Villages were napalmed and poppy fields were booby-trapped with landmines. By 1968, in response to a growing understanding that this repressive approach was swelling the insurgent support base, Thailand began supporting the socio-economic development of highland areas. In many areas, opium cultivation was essentially decriminalised until farmers could access profitable alternatives. The result was an immediate reduction in the insurgency and a somewhat slower reduction in opium cultivation.

I am not naïve enough to suggest that socio-economic development alone can prevent and contain all illicit enterprise and organised crime. Nor do I argue for the cessation of all law enforcement. Instead, I am simply suggesting that law enforcement should be selective, respectful and undertaken with forethought of potential unintended consequences. Here, historical research can facilitate evaluation of past mistakes and failures as a result of a purely repressive approach.

Dr James Windle is a lecturer in Criminology at University College Cork. His research focuses on illicit drug markets, illicit enterprise and street gangs. He is author of Suppressing Illicit Opium Production: Successful Intervention in Asia and the Middle East (IB Taurus, 2016) and co-editor of Historical Perspectives on Organized Crime and Terrorism (Routledge, 2018).

Main Image Credit: Anntinomy, via WikiCommons.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of RUSI or any other institution.