As cartels in Mexico have evolved under pressure, so too have their presentation, methods and goals.

Forcing Change

Sharing an over 2,000-mile border with the largest cocaine consumption market in the world, early Mexican drug trafficking organisations (DTOs) leveraged nearly a century of smaller-scale smuggling experience to streamline trafficking into the United States (US). Despite conflict between the dominant Guadalajara Cartel and smaller DTOs, Guadalajara maintained control, mitigating full-on war and internal challenges. In this early period, the cartels’ strict hierarchical structure bore resemblance to even licit industries, placing enormous value on cartel leaders. The relative ease of business characteristic of Mexican cartels in the 1970s and early 80s was bolstered by the Mexican government, ruled by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Over the course of the PRI’s 71-year reign, cartels exploited endemic corruption and benefited from tacit agreements with the Mexican state, permitting operations in certain areas and occasionally brokering peace between groups.

A pivotal shift in scope and intensity of the war on drugs came in 1985 with the murder of US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) agent Enrique ‘Kiki’ Camarena. Kidnapped, tortured and killed by suspected cartel enforcers in Guadalajara, the event sparked an aggressive response from the US and Mexico. The Guadalajara Cartel’s leader, Miguel Gallardo, was arrested in relation to Kiki’s death and extradited in 1989. Gallardo’s arrest marked the first high value target (HVT) that later formed the US’s ‘Kingpin Strategy’ aimed entirely around disabling organisations through the arrest of HVTs. Gallardo’s own Guadalajara Cartel splintered into the Juarez, Tijuana, Sonora and Sinaloa Cartels. In Michoacan, La Familia Michoacana devolved into 14 competing groups. The highly centralised intra-cartel hierarchy had begun dissolving, trending towards a form of hyper-violent drug trafficking franchises in which the new DTO’s value rested in their ability to defend – and capture – territory. The new cartels, therefore, each vying for market share, territory and survival, organised and equipped themselves for competition.

The fierce inter-cartel competition drew more blood, publicity and criticism. By 2006, Mexico’s long reigning PRI lost power to Michoacan-native Felipe Calderón whose campaign was propelled by promises of law and order. Calderón wasted no time, dispatching 6,500 Mexican soldiers to violence plagued Michoacan. Mexico’s cartels, unwilling to submit, fought back. A relatively safe country in 2006, by 2010, President Calderón admitted having witnessed Mexico’s bloodiest year on record. By 2011, Mexico’s homicides had jumped threefold.

New and Emboldened Trends

As near-record violence persists in Mexico, videos of armoured caravans, high-calibre, weapons and uniformed soldiers have been making rounds domestically and abroad. The sight of military-grade hardware rolling through Mexican streets has for decades been familiar for residents in the country’s beleaguered, violence-ridden regions. However, the videos do not show another convoy of Mexican police or Marines like those sent in by President Calderón in 2006. These soldiers sport a patch marked ‘CJNG’, the acronym of the ultra-violent Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación. These professionalised narco-paramilitaries proliferated in Mexico, notably with the arrival of Los Zetas. Originally a group of 32 defected Mexican commandos recruited by the Gulf Cartel, the paramilitary outgrew and turned against their parent organisation. Los Zetas’ brutality would only be matched when a counter-militia, Los Matas Zetas, an early extension of the CJNG, declared war.

The CJNG – now one of Mexico’s two biggest cartels – have employed their paramilitary muscle in an historically uncommon way. In Michoacan, their insurgent-like sieges of towns and extensive use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and drones has analysts drawing comparisons to militant groups like the Taliban. The CJNG has not limited its signature violence to rival cartels or the legalised, regional self-defence groups. Rather, it has escalated attacks against police, the military and government officials evidenced by an attempted assassination of Mexico City’s Police Chief in 2020 and the high-profile shooting down of a military helicopter in 2015. Whilst the CJNG’s paramilitary style represents an extreme relative to other cartels, such as their rival Sinaloa Cartel, the violence is widespread.

A safe house storing cartel ammunition and weaponry.

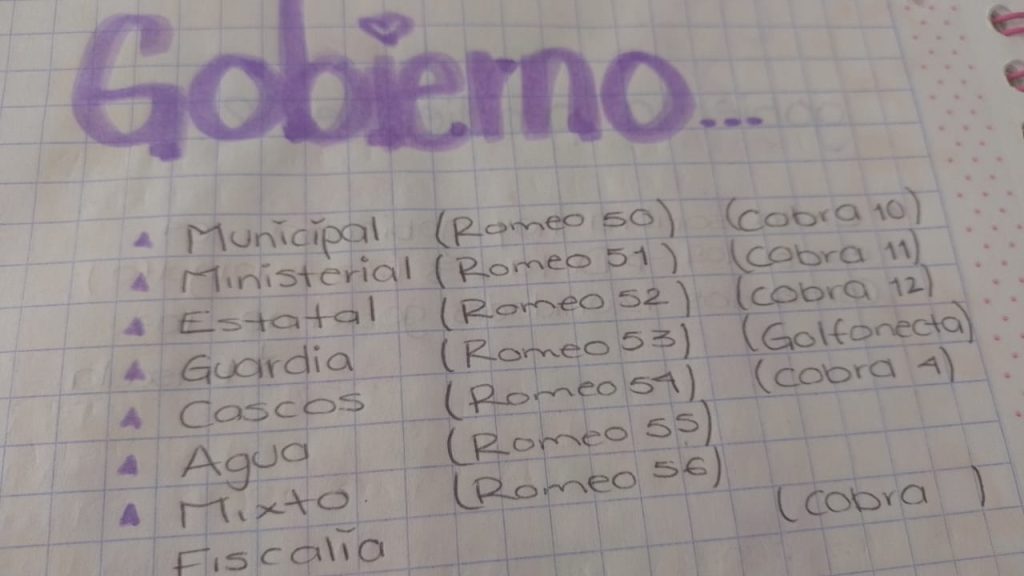

The intensification of violence against the state marks another trend. Apart from law enforcement, cartels have systematically targeted politicians and candidates across the country. In the 2018 elections, a minimum of 128 candidates and campaign workers were assassinated by cartels, a stark increase to the less-than 20 candidates killed in 2012. Recent elections in 2021 saw over 88 politicians and candidates murdered, largely at the local level.

Hybrid Warfare: Nearing ‘State Capture’

These shocking trends of cartel violence are not random nor nonpurposive. In fact, comparisons with Colombian cartel trends in the 1980s and 90s indicate these escalations to be signs of emboldened, risk-taking cartels seeking to significantly weaken, co-opt or capture the state. Cartel hybrid warfare in Colombia featured massively destabilising assassinations against presidential candidates, the taking down of a commercial airliner and a suspected conspiracy to storm the Colombian Palace of Justice. These acts formed part of the cartels’ political messaging – a critical element of hybrid warfare – to force policy reversal, cancel extraditions or warn against encroachment by authorities. The recent trends of violence in Mexico can thus be understood as political discourse through violence. The CJNG’s paramilitary posture, beyond its tactical value, can be framed as a means of deterring Mexican state intervention. By promising high-intensity and high-casualty conflict, the paramilitarised DTOs have at times succeeded in establishing narcostates. The mass political killings have attained equal effect, likely stoking fear and apathy in officials and candidates.

Such hybrid warfare has seen success in controlling or installing favourable officials. Malleable officials allow cartels to ward off investigation and turn the state against competition. Such was the case in Veracruz in 2016, where the CJNG gained control over the local government and forced Los Zetas out – a blow from which they were never able to recover. There also exist incentives to topple or weaken the state that have been bolstered by the cartel’s recent diversification, potentially accelerated by the COVID19 pandemic. Whereas in the Gallardo era of the 1970s and 80s, cocaine and marijuana production and trafficking represented the lion’s share of revenue, cartels today have expanded extortion rackets, as well as diversified their activities to include human trafficking and synthetic drugs such as Meth and Fentanyl. Cartels have further ventured into new markets, evidenced by the Sinaloa Cartel’s emergent control over Mexican fisheries.

As the violence persists, it may be important to recast the assaults – and their purpose – as a form of paramilitarised, necessarily political, hybrid warfare rather than traditional criminal gang turf wars. In doing so, analysis of shifting tactics cannot be made independent of the history from which they spawned. This becomes particularly valuable as counterinsurgency campaigns are proposed as a solution, particularly by Mexico’s northern neighbour. Such strategies run the risk of further accelerating cartel’s adherence to hybrid warfare and deepening Mexico’s violent spiral.

This blog is the second in a three-part series in partnership with photographer and director Eduardo Giralt. The series is intended to shine line on the realities and trends of drug cartels through a combination of images and analysis.

Eduardo Giralt is a field researcher, photographer and director where his in-country work gives an inside look into Mexican drug cartels and cartel life. Eduardo directed and released ‘The Weak Ones’ (2017) and ‘Los Plebes’ (2021) for which he was nominated and awarded Best Director at the Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema. He has also released a photobook titled ‘Sicario Warfare‘.

Elijah Glantz is a Research and Project Officer Assistant for RUSI’s Organised Crime and Policing research group. His research interests include criminal governance and illicit economies in conflicting and fragile states. He is an MSc candidate in Conflict Studies at the London School of Economics and holds a BA in Political Philosophy from Sciences Po.

All images and captions provided by Eduardo Giralt.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of RUSI, Focused Conservation, or any other institution.